Resources - Blog

Back to basics

Written for The Guardian’s new Resource Efficiency Hub, Great Recovery project leader Sophie Thomas explores how waste is a design flaw, and how we need to rethink products to ensure fewer end up on the mountain of e-waste.

Six months in and The Great Recovery programme, run by the design team within the RSA’s Action and Research Centre has begun in earnest. Our investigation into new design methodologies for a circular economy has thrown up some big very complex challenges. Trying to consider the re-design of even a fraction of the 600 million tonnes of products consumed in the UK is a pretty daunting task.

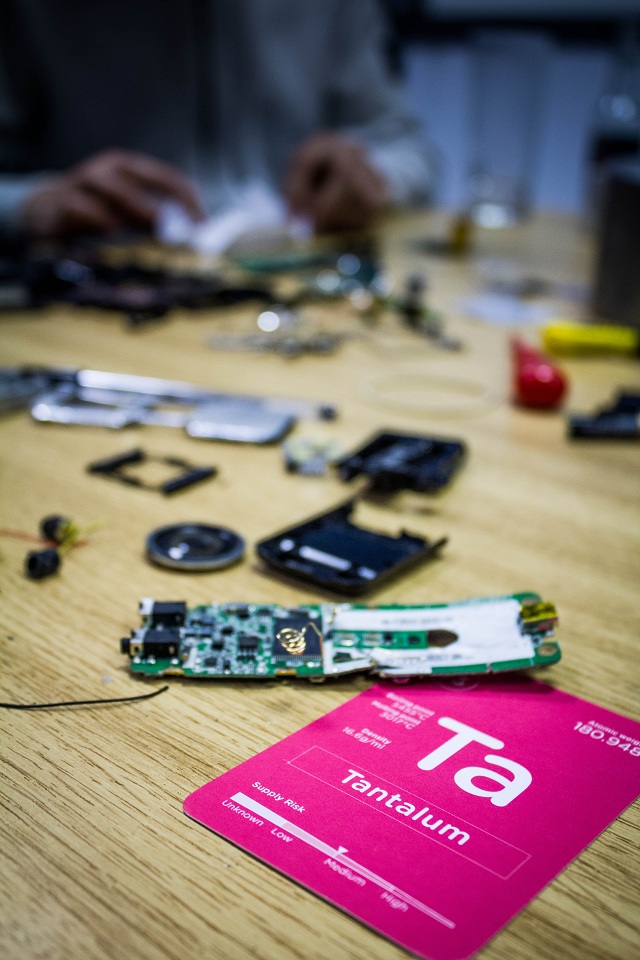

We are a linear nation with only 19% of the materials in those products being recovered and re-used in the UK. Our current best practice for recycling electronics is to sort, crush then export to somewhere else to refine. Of the 40 odd elements in the ingredients list for each of appliances even the best recovery facilities in the EU can only recover at best 16. A designer may come up with the best design for disassembly but with our current infrastructure there is still a very high chance it will end up on the e-waste mountain. The answer lies in the re-design of the ‘material to manufacturer to consumer’ system and making it circular.

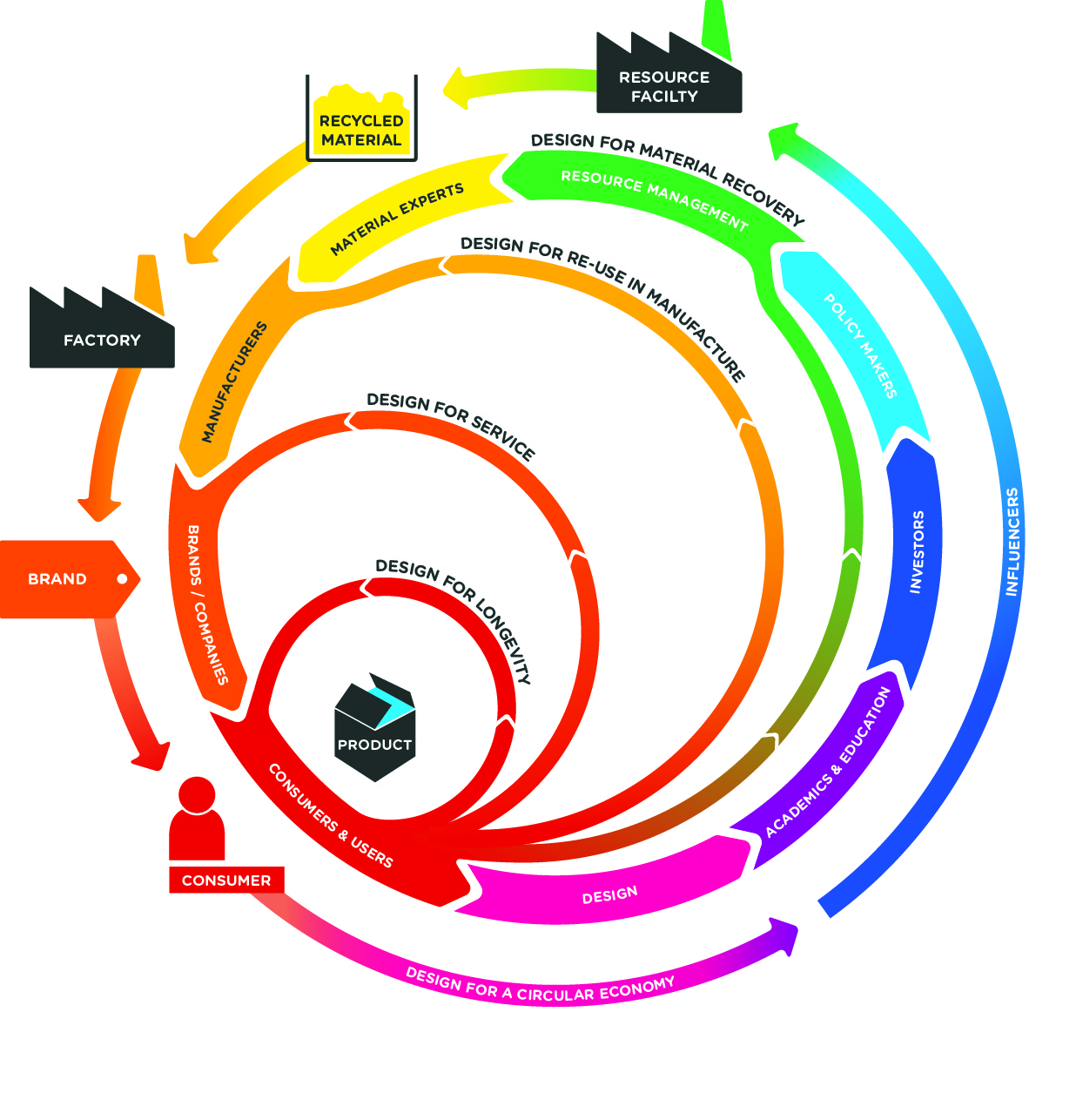

Resource scarcity feels like a problem that should be solved by technology or sorted by government. The reality is that this challenge is so big and complex everyone must pick up the gloves. When approx. 80% of the environmental impact is locked in at the concept design stage[1] the reason why we bring together designers, technologists, chemists, waste experts, manufacturers and businesses to face the mountain is clear. The material recovery path must lead the design process and this process must be co-created by all those that are part of the supply and recovery chain.

Our investigation has focused on re-imagining products by looking at their material flow cycles; taking emphasis off the product itself which, you could say ‘borrows’ materials for a period of time shaped into a form before ideally releasing them back into the cycle at the end of the product’s life.

We do not currently design or manufacture like this. This becomes obvious when you take these objects apart and try to split out the ingredients. Toothbrushes, disposable coffee cups, books, TVs, houses; all designed and manufactured with endless lists of materials that are moulded and fused together by machines on efficient production lines, but in the process making them impossible to disassemble so that materials can be recovered.

Our workshop participants swapped their studios and offices for rooms that overlooked enormous waste mountains deep inside packaging recycling plants, textile sorting centres and electronic waste recovery facilities. We spent days in engine re-manufacturing factories, material science laboratories and went down a disused tin mine in Cornwall. These places were physical demonstrations of the potential value in resource and the current best, but by far complete, practice of recovery. Those that came to the workshops walked away with a new sense of reality that came to be known the ‘Fear, Farce and Challenge’.

1. The Fear is a reaction many of the designers have expressed when they are asked to ‘look at the product they spent months designing, launched to much fanfare a year ago that now sits in the mountain of rubbish’.

Waste is a design flaw. Current design process only takes us to the point where the consumer picks it from the shelf and takes it to the cashier. We rarely consider what happens post-consumer and when we do our knowledge is out of date and often incorrect. Designers hide behind the brief saying they have no power, they only deliver a service – so brief writers were invited to the workshops too.

2. The Farce is the growing realisation that in order to make these appliances we had to source piles of raw material (including some from war torn areas, or perhaps extracted using slave labour), invest in numerous production processes around the world and ship them from continent to continent incurring many ship and air miles’.

A new laptop can cost you under £300 but if you track the flow of raw materials from the mines to the factories and distribution centres the average computer travels the equivalent of three or four times around the world before they end up in the hands of the customer. Designers have to work with the global market system and it would be naïve to think otherwise but understanding material flows and designing to circular economy principles could result in more local and less carbon intensive production. Traceable supply chains designed around transparency can enhance resource security and support the corporate social responsibility objectives many large manufacturing businesses have adopted.

3. The Challenge is to re-think the design of our products from first principles. Pull an item off the waste mountain and take it apart. Understand what is in the product, where the materials came from and why they are there? Most objects disassembled at the Great Recovery workshops were not generally made to be taken apart. Take LCD TVs that have hazardous light tubes full of mercurial vapour, which must be taken out by hand before they can be put through the crusher. Some models have over 250 screws requiring 15 different screwdrivers to undo before you can extract anything.

The process of deconstructing an object (also known as ‘tear-down’) in order to understand how it has been put together and how it can be improved is a well-established design tool. Many Japanese electronics companies train new designers on the recycling floor before they are allowed to enter the design studio. Many designers talk about their misspent youth tearing apart anything they could lay their hands on with nostalgia and joy. It engages the practical maker/creative part of the brain and even the hardiest consultants and heads of finance attending the workshops had glints in their eyes when handed a pair of safety specs and a hammer.

This newly re-set vision allows you to see things in a different way. Some things become ridiculous – a disposable electrical toothbrush becomes an electrical appliance with a 4-month life designed with multi-moulded unrecyclable plastic, a long life battery and almost as many elements as a mobile phone; some things become opportunity – a laptop is for life and is fixable, upgradable and eventually will be sent back to the manufacturer for dissassembly and re-use, but everything seems to need re-designing.

The Great Recovery is supported by the Technology Strategy Board that is funding 50 feasibility studies selected through their competition on re-designing for closed loop systems. www.greatrecovery.org.uk

[1] Design Council