Resources - Blog

Deconstruction #2: Mobile Phone

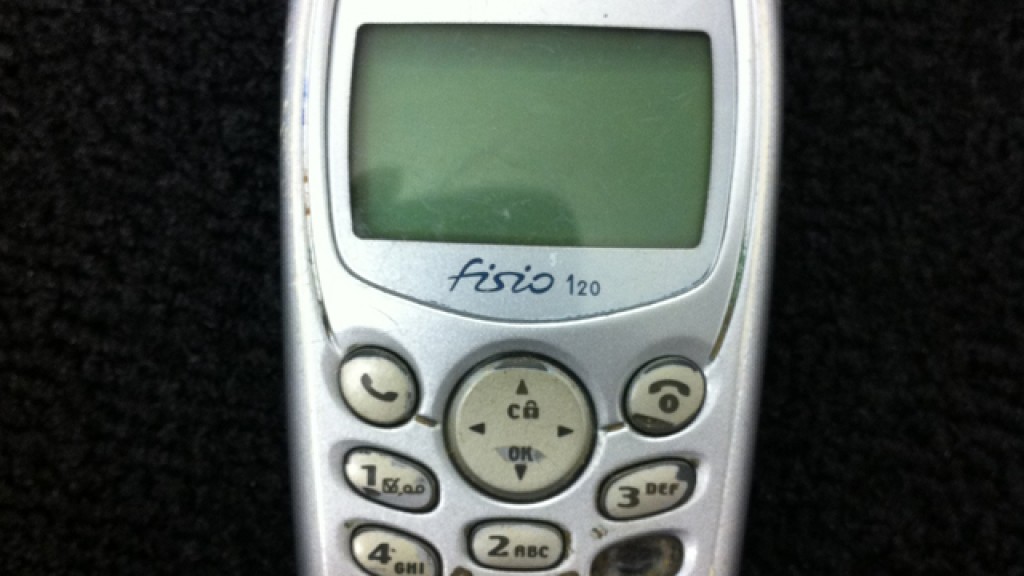

The next item in the firing line of our deconstruction series is an old phone. It’s been sitting at the bottom of a drawer, ‘just in case’ it was needed, but it hasn’t been used in a long, long time. This phone isn’t alone in being popped to one side for years on end. On average, each UK household has 2 unused or old mobile phones stored away somewhere. That’s a massive 49 million handsets that are simply sitting in our homes. So what actually are we storing in our cupboards (apart from a few text messages and an old photo of your cat?).

We took apart an old phone at a FairPhone workshop to try and find out.

Inside a basic old handset, we discovered layers of metal and circuit board, all made up of a huge 35 types of metal, including copper, tin, cobalt and gold. A recent study suggests that one tonne of ore from a gold mine produces just 5 grams of gold on average, whereas a tonne of discarded mobile phones can yield a massive 150 grams.

Digging a little deeper, we discovered that a tiny part of the phone – the capacitor – contains the element Tantalum. The name Tantalum comes from the metal’s unusual quality of repelling liquids, much like Tantalus, a figure in Greek mythology who was forced to stand in a pool of water that remained constantly out of reach when he tried to take a drink. Tantalum can be found in nearly all of our electrical goods – mobile phones, lap tops, hard drives, PlayStations… and the list goes on.

Derived from the metallic ore Coltan, which is mainly found in the Democratic Republic of Congo, its ‘medium risk’ labelling and its rising value has made Tantalum a huge catalyst in the on-going Congo war. A recent report by the UN has claimed that all the parties involved in the local civil war have been involved in the mining and sale of Coltan. In the province of Katanga alone, an estimated 150,000 work in the mines, including 50,000 children and young people, some as young as seven years old.

At this year’s 100% design, Mark Shayler looked in a little more detail at the global supply chain of our electrical goods, and revealed that up to 64% of the world’s Coltan supplies are estimated to come from the Congo. Now think back to those 49 million mobile handsets that are sitting unused around the country. If we were able to recover all of the Tantalum from these, we could make 49 million new mobile handsets that wouldn’t need to rely on a ‘conflict metal’.

FairPhone is working to bring a ‘fair’ smartphone onto the market. This means a phone that is made “entirely out of parts and utilised without harming individuals or the environment.” They are working to find new ways to produce these necessary raw materials by questioning every stage of the process; finding fair mines (or investing in their creation) and recycling our existing raw materials. If we could roll out this thinking beyond our mobile phones, and apply it to all of our electronics, questioning where elements have come from and where they will go, we will be one step closer to a circular economy.

It’s time that we all begin to question the products that we are consuming. To find out more about e-waste, try your hand at taking a mobile phone apart, and learn how you can make a difference, come to one our e-waste workshops at SWEEEP electronic recovery facility, Kent on the 16th November, or at S2S in Rotherham on the 21st November.

Why don’t you take something apart and see what you discover? To contribute to our deconstruction series, contact hilary.chittenden@rsa.org.uk