Lewis Foster is a designer/filmmaker and a recent graduate of LCC. He is particularly interested in what goes into the products we consume on a daily basis.

In my final year I worked on a project inspired by Leonard. E. Read’s essay I, Pencil looked at unravelling the web of manufacture in the production of a pencil. Critically the aim was to highlight how little we know about the products that surround us by utilizing the seemingly simple example of a single pencil. Once I started to scratch the surface in understanding the pencil’s story, the sheer complexity it fascinated me.

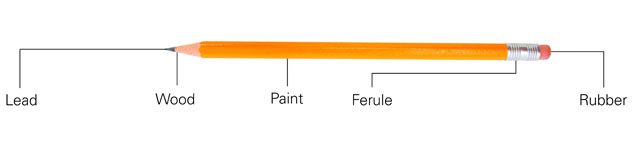

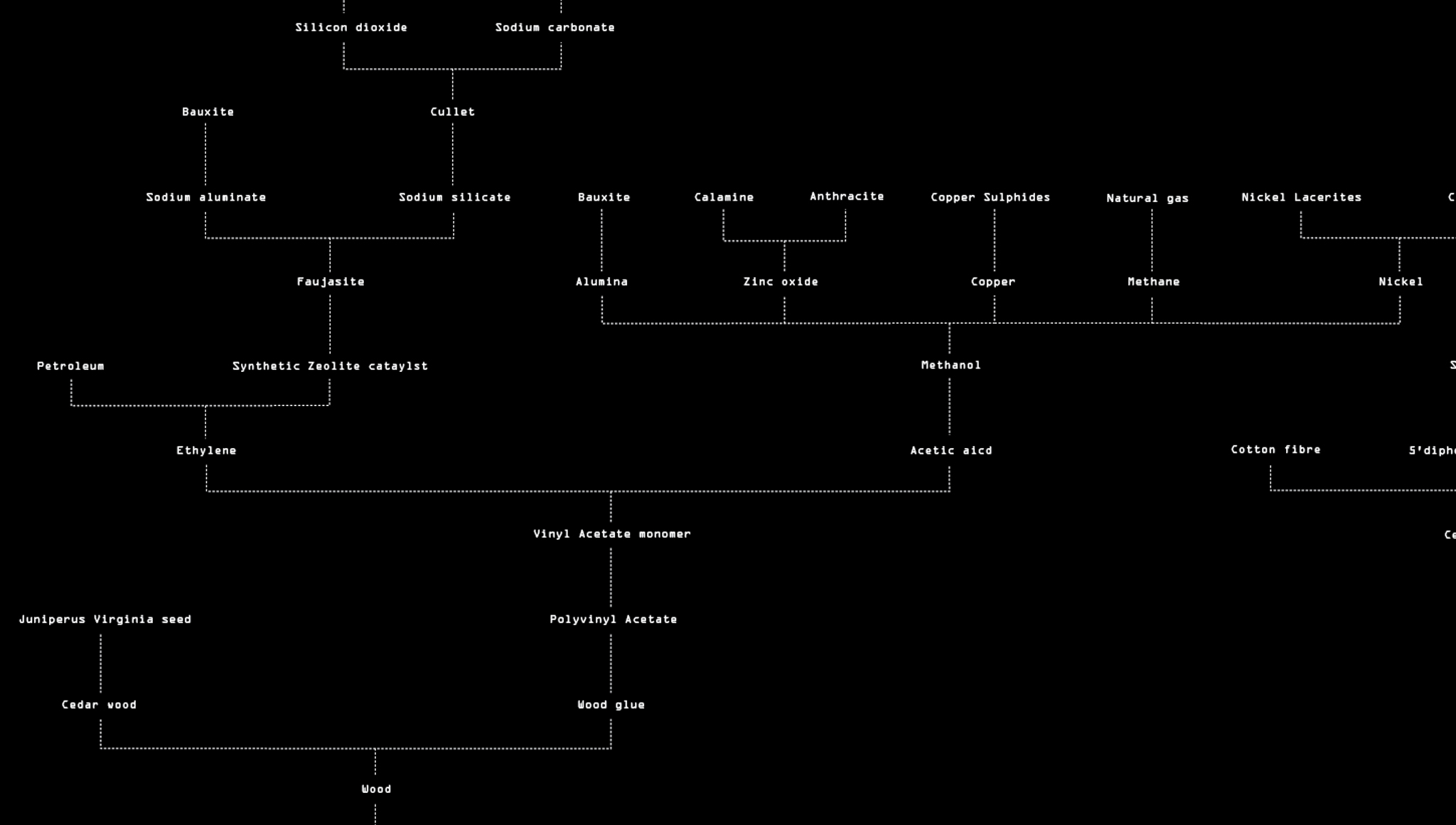

Starting with each part of the pencil I began to trace back it’s origins. The pencil I was investigating had five parts: the lead, the wood, the paint, the ferule (the metal holster containing the rubber) and the rubber. Step by step, I began to map out the ingredients of a pencil back to its raw materials: the wood of the pencil is most likely Cedar wood, the sourcing of which is easy enough to imagine. You need a seed and land which is managed by a Forester. You need machinery and a specialised workforce to cut and transport the tree, the wood then needs to be processed, cut into slats at a saw mill, then dehydrated and finally shipped to the pencil factory. However each pencil has two parts of wood glued together and the glue is far more complex. Wood glue is usually a form of polyvinyl acetate, which is produced by reacting Ethylene and Acetic acid; to form Ethylene you need petroleum and a synthetic zeolite catalyst and so on and so on. For wood glue alone you need ten raw materials: petroleum, bauxite, sea water, calamine, anthracite, natural gas, limestone, copper sulphides, nickel lacerites and bituminous coal. All of which have to be sourced, purified and reacted with each other with a specialised workforce, machinery from different parts of the globe.

I filtered all this information into a 4 metre long family tree illustrating every ingredient that goes into the production of a pencil, but coincidentally it gives an insight into the otherwise invisible connections of manufacture. Little does the soya bean farmer or the salt miner know he has a hand in the production of the pencils he uses everyday and more importantly the pencil manufacturer doesn’t know they indirectly employ the soya bean farmer or the salt miner.

This is the challenge for a closed loop, circular economy. We need to first understand what our product is. This understanding has to go beyond its primary constituents, we have to examine deeper into exactly how each material of our products are formed in order to implement a cradle-to-cradle approach.