Resources - Blog

Redesigning the Razor – Teardown

This is part three of the series of blogs following product designer Sebastian de Cabo, as he designs a razor to work within a circular economy. This instalment concentrates on the disassembly of a variety of razors and accessories in order to then carry out a Life Cycle Assessment and to inform future design decisions.

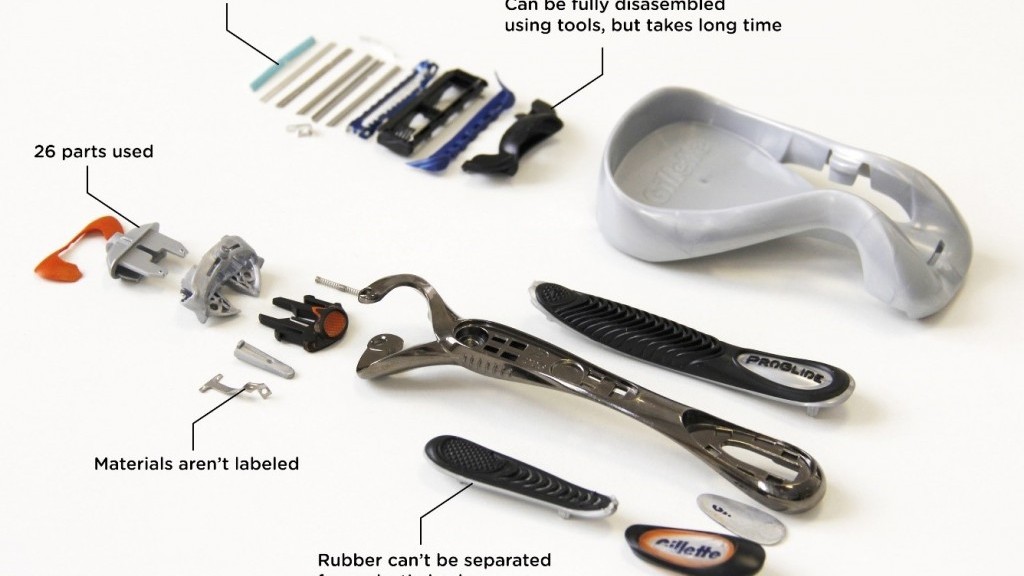

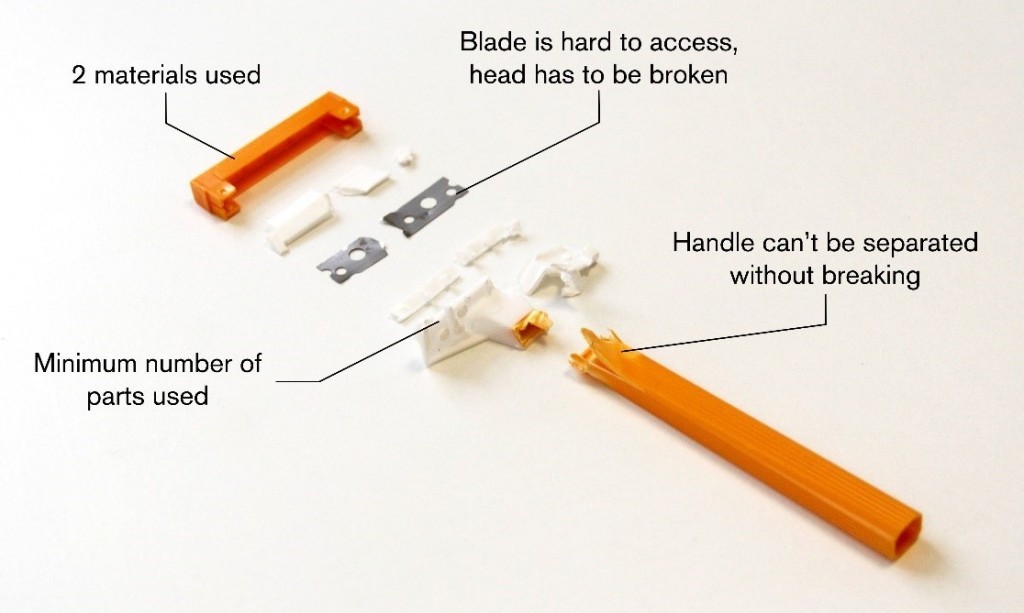

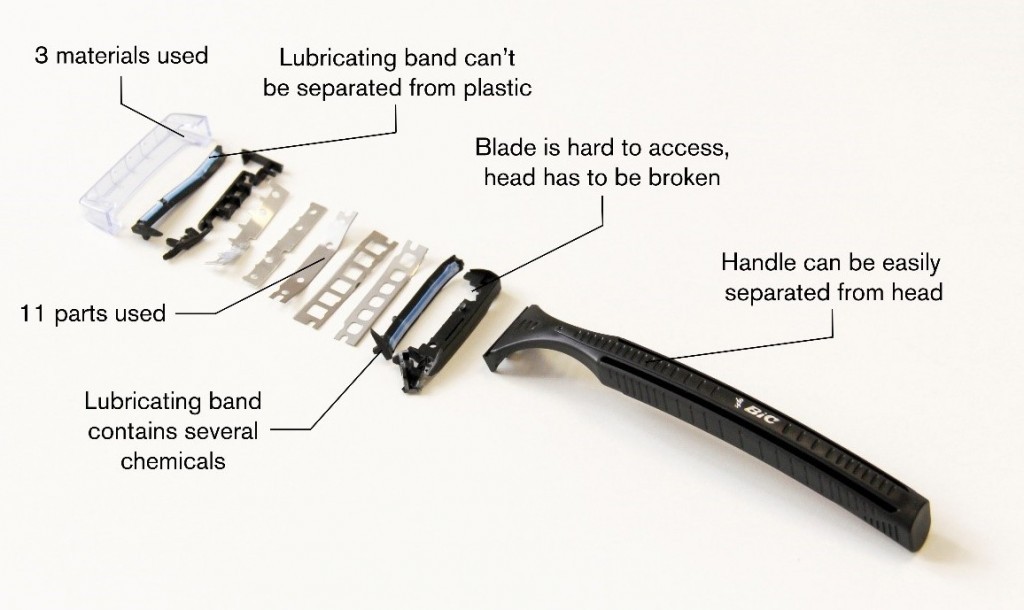

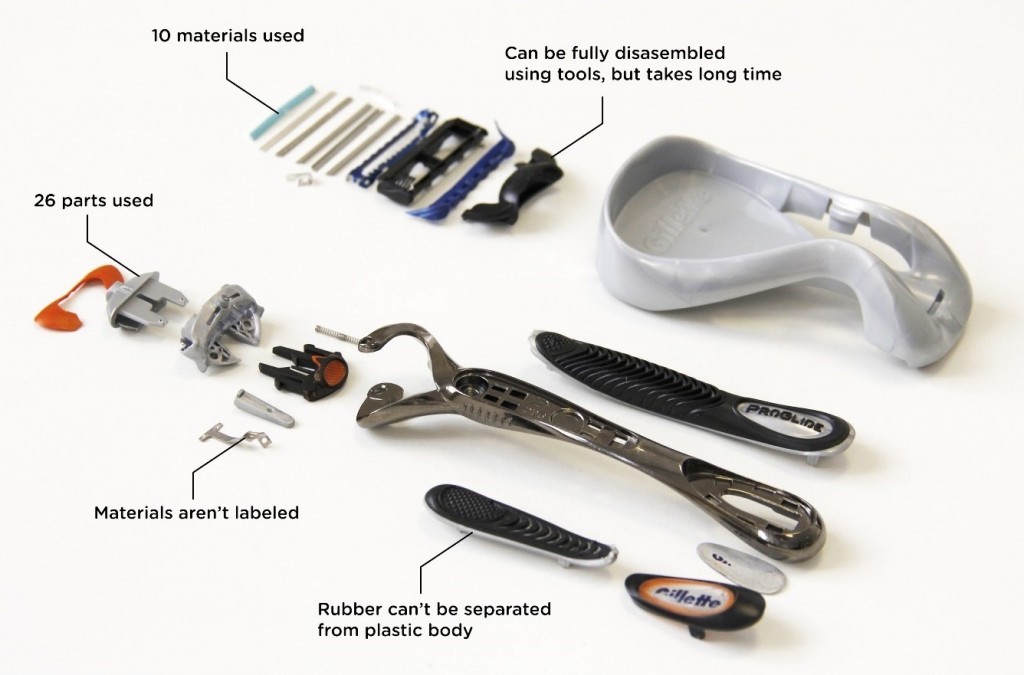

Razor Teardown

Tearing down a product is an illuminating process for the designer in search of circularity. It is an excellent way to analyse a current product and identify key information about its production: how many materials and parts it is made from, and how these parts are assembled.

Leading on from this, and vitally important for circularity, it enables a prediction to be made about what will happen to the product when it reaches its end of life and enters our waste system.

To be recycled effectively, materials needs to be separated. A product that is difficult to disassemble, either by hand or mechanically (shredding), is unlikely to make it into a recycling stream and much more likely to be landfilled or incinerated. Its valuable materials lost.

You will see in the disassembly pictures below that all the razors were hard to separate manually. The cheapest, a disposable BIC, couldn’t even be separated without breaking it.

The reason for this? Products are created by designers and engineers seeking to solve the brief they have been given. For fast moving consumer goods such as the razor, this often means creating a product which combines the demands of high performance, low price and high speed. With these emphases it is unsurprising that difficult disassembly is a by-product.

On the other hand, if the razors are going to be shredded and then the pieces of materials separated, the product wouldn’t need to be designed for easy disassembly, which could be the reason why the BIC razor is attached together the way it is.

This means that razors don’t have to be designed the way they are, their design would be quite different if circularity was included in the brief since the beginning. We will use the problems encountered during the disassembly stage, and convert them into design challenges in order to improve our final design of the razor.

Possible solutions for the disassembly problems:

•Minimise the number of parts – instead of using 26 different parts.

•Minimise the number of materials – best option could be to use just one material which is fully recyclable at its End of Life without being downcycled.

•The impact created by the manufacturing method, and the difficulty in separating the materials at the waste management site would be considerably reduced if the blades were attached by snap fits or push fits instead of being spot welded 17 times each. One reason why these cartridges can’t be recycled is because the metal strips are so thin and stuck together that separating them would be labour and cost intensive.

•Labelling the materials would make it easier for customers to know where the razor should be thrown (so it can get recycled) and easier to sort the materials and parts out at its End of Life by the waste manager.

The best product in terms of circularity out of the ones analysed is the classic double edge safety razor. It contains a minimum number of materials and parts which can be disassembled in under a minute without any tools (just by hand). The blade is easy to access and replace, so the body can be kept for a long time instead of getting thrown away. This version wouldn’t probably last as long due to the cheap materials used but a metallic one would last for a lifetime. Finally the blade can be recycled so this product wouldn’t make as much impact as the cartridge-based razors (or we’ll find out during the Life Cycle Assessment).

The tearing down process of these razors has confirmed for me the need for our new design to be made in a way which is easy to assemble at manufacture and at the same time easy to disassemble at the end of life, in order to increase recycling efficiency and also to make it easier to repair and extend the products lifetime.

This project is a collaboration between the Great Recovery Programme and Fab Lab London.