Last week another BBC documentary caught my eye. “The Hunt for Britain’s Metal Thieves” was an action-packed-shaky-camera –police-chase-o-rama of a show, but hidden beneath the ‘police-camera-action’ style footage was a very serious message.

We’ve all heard of lead being stolen from church roofs, and probably all been delayed due to theft on the railways – I was left fuming without internet for three weeks last year when telephone cabling was stolen in my area, but despite this I was still shocked by the extent of metal theft that is currently happening throughout Britain.

Metal is extremely, extremely valuable. In 2011, an estimated 15,000 tonnes of metal were stolen. In just the last 3 years, £13million worth has been taken from British Railways alone, including copper cables, clips that hold the track down, earthing straps, overheads, power lines and even the track itself. A former metal thief, ‘Matt’, revealed that he could get up to £1000 to £1500 in just one nights work.

I think the most shocking footage in the programme was from 2011, when in Castleford, Yorkshire, 3 terraced houses exploded, with fire crews forced to evacuate and hundreds of thousands of pounds worth of damage caused. It transpired that this was due to thieves targeting overhead electricity cables for their copper. Cutting this cable had removed the earth of the electricity supply, which was diverted into the metal in the structure of the houses. The now electrified gas pipes heated up and caused an explosion. Amazingly, no one was seriously hurt, but for a piece of copper worth £40, this could have had some truly tragic results.

In Sutton, Surrey, a more unusual form of metal theft is taking place, in the shape of man hole covers. A huge 50 covers were stolen in just one weekend, and as soon as this number crept up to 200, the council knew that they needed to do something about it. Instead of using heavy metal covers, they are being replaced with replica plastic models, which are of far less worth. On top of man hole covers, 1 war memorial per week is vandalised for its bronze, and there have been cases of silver sanctuary lamps in churches being stolen in broad day light.

So what happens to all this metal once it has been nicked? As soon as it’s back in its ‘raw’ form (i.e. bundles of copper wire, all casing removed) there’s no way of telling where it’s come from, so scrap yards – an industry worth over £5 billion in Britain – have difficulty identifying whether they are buying stolen goods.

When metal leaves the scrap yards, it is loaded onto containers, a huge amount of which are shipped to countries such as China. There are 3 million containers a year of scrap metal shipped from Felixstowe port alone, and in 2012, 420 containers were searched along the East Coast of Britain revealing half a million pounds worth of stolen scrap metal on its way to China, Africa and India.

Paul Robinson of the London Metal Exchange explained how in the last decade, metal prices have risen between 400-500%. 10 years ago, copper was trading at around $1,500 per tonne, but by 2011 this figure had risen to $8,500 per tonne. Why is this growth so rapid? “Consumption has grown because of the growth of China. In 2011, China consumed as much copper as Japan, North America, Europe and Russia combined.”

And is this set to settle any time soon? No, says Robinson. Even when China stops growing, there will be countries like India, waiting to have their turn. Our metal prices are going to continue to rise.

So what can we do to stop this crime? Preventative measures are already being put in place to make it harder to sell stolen metal – since 2012, scrap yards have been required to detail transactions and ask for ID, and cash payments are being discouraged. But is this enough? As long as metal is worth so much money, and so readily available on our doorsteps, there will always be people to take it.

But where is this theft going to stop? Sweeep in Kent told us how they have to be extremely careful of bales of scrap plastic casing (from computers etc) being stolen, as the cost of plastic is now soaring, and last week at LMB Textiles recycling in East London, we heard all about the huge amount of organised crime there is surrounding recycled clothing. Gangs will know when ‘collection days’ are for charity bags of clothes, and get there just before them. Textiles recycling ‘bins’ are a regular target for crime, with second hand clothing selling for a premium in Africa. We are seeing reports of people trapped inside these recycling bins while trying to steal the clothes inside, and even ‘dangling children’ into the bins to get at the valuable textiles.

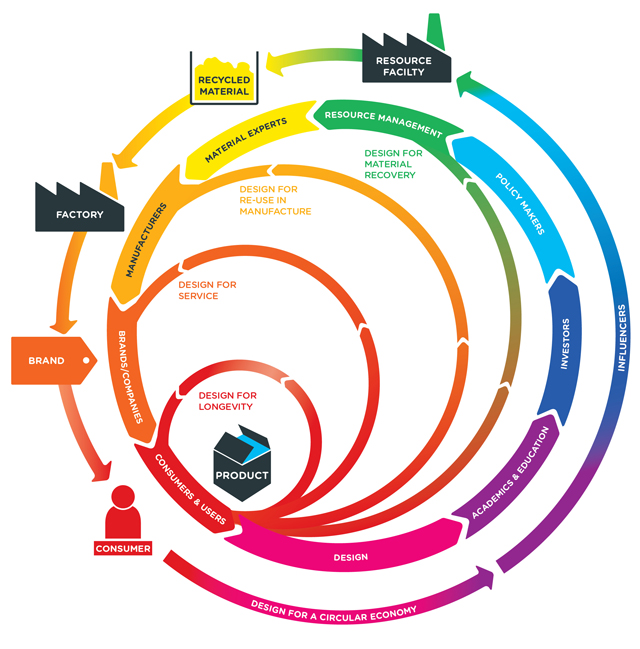

Clearly this is not just an issue around metals, but an issue around material security and scarcity as a whole. So how could re-designing for a circular economy attempt to solve some of these issues? There’s no doubt that materials are going to become any less valuable, so we need to reassess how we use them and what happens to them at the end of their life. These stolen materials are being ‘recycled’ – but not by the right people at the right time. At the beginning of the design process, we need to assess the products life and design accordingly. This is why we have developed our circular design map. Designing for longevity is not always the answer, and clearly is not suitable for every case. We can also design for a service model, for re-use in manufacture or for material recovery.

Our need for a more circular economy is driven by economic factors. Risk to our supply chain is increasing, and the cost of materials is rising sharply, putting pressure on businesses to change. We need to shift towards more circular systems and good design thinking is pivotal to this transition.

“The Hunt for Britain’s Metal Theives” was aired on BBC One, 12 February 2013. All images credited to the BBC.